My “Lolo” – With Gratitude & Love

by

From my podium at the front of the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine lecture hall, I see my grandfather. My Lolo. He’s smiling and I feel his energy, especially his radiant heart as he subtly nods and our energies connect with a shared joy and a secret acknowledgment of what has now become our sweet, private ritual.

I nod back, and with an intentional taking in of a tandem deep breath, I say a prayer of acknowledgment.

“I’m here, Papa. We did it. I may not be the brain surgeon that you wanted me to be, but I’m teaching them.”

And then I begin my lecture. But not before I quietly thank the man who not only saved my life, but who helped create every aspect of my life. My Lolo. My sweet, loving, brilliant, strong, and always-present, Lolo.

My grandfather emigrated from the Philippine Islands when he was 17 years old. Whether driven by political unrest, or familial unrest was never discussed. What was known was that my grandfather was the first born son of thirteen children, born to a peasant farmer and his subservient wife who struggled daily amid an existence of poverty, political dominance, and lack of opportunity.

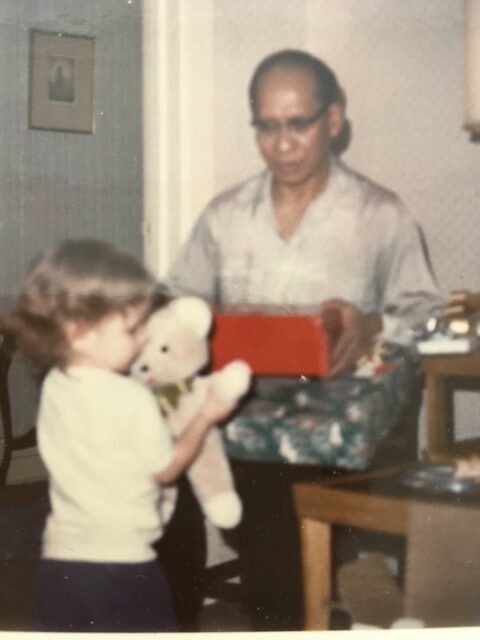

I knew my grandfather simply as, “Papa.” My Lolo who could be found without exception every morning gazing out at his award-winning garden, within his small city allotment, located beneath the elevated train tracks of the Chicago transit system. A system that screeched and pounded across our backyard, and within our lives, during my early years.

We lived in a three-flat apartment building that allowed me and my two older sisters to run up the back stairway and into my grandparents’ apartment at will, where life was normal. The house was clean. I would be fed. Mostly, I would be loved.

I have no memory of my early life without my grandparents, or for that matter, my beloved Filipino Godfather, Augie. Angels who stepped in to help raise us after my mother began having babies, when she was fourteen years old.

So close were we that I not only called my Lolo, “Papa,” but I referred to my Italian grandmother as, “Mom.” As a psychologist who focuses on attachment and complex trauma, I can say with abundant certainty that I would not have emotionally survived, if not for the foundation of consistency, nurturance, and love that my grandparents provided.

My meals were provided by my grandparents, my body was washed by my grandparents, and I was held in the loving arms of my Augie as he picked my sisters up from school.

Whether because my parents were so immature and so psychologically deficient in what they had to offer, or because my grandparents were so incredibly generous and loving of heart, my sisters and I came to cherish every sentiment of family, and nurturance, and culture that my grandparents represented.

This included, most significantly, my grandfather’s Filipino heritage.

I grew up feeling Filipino. No, embracing and embodying the Filipino identity that was mirrored in my sweet Lolo’s skin. I was soothed each night to “Planting Rice is Never Fun,” a Filipino folksong that my Lolo hummed as he rocked me to sleep. I enjoyed pancit and pork and vegetable “mixtures,” which were my Filipino dinner staples. And when I came of age, I mastered the family secret recipe for chicken adobo.

Chicken adobo, the iconic Filipino dish that was always present and has come to define celebrations and holidays for multiple generations within my family. And which continues to be a requested favorite of my now grown daughters, who still beg, “Please make turkey adobo!” every Thanksgiving, much as I begged my Lolo to make turkey adobo instead of the typical American fare.

I still have fond memories of sitting with my Lolo at the kitchen table as he carved the vinegar and oil-based bird, and I “picked” at the succulent bones as we chatted. A story I shared with my now-husband the first night I made him chicken adobo, a traditional gesture of Filipina women in my family, that signaled the relationship was serious!

But food was not the only aspect of Filipino culture that shaped me.

Education and knowledge, especially pursuits within the medical profession, were Filipino values that my Lolo seeded within my impressionable soul.

While no one in my family had ever gone to college, I always remember my Lolo sitting holding a book in his hand, usually a literature classic such as Dickens or Hemingway, or a scientific-based book, such as his many textbooks on botany, veterinary studies, and medicine.

One of my Lolo’s most ardent dreams was to be a doctor, a medical physician. While this is another topic my proud, introverted Papa never discussed, his long-held personal goal of becoming a physician was tragically and repeatedly interrupted. First, by the environment of post-World War II prejudice that engulfed the American zeitgeist and negatively impacted opportunity for all Asians. And second, due to the unexpected financial strain that came with surprisingly needing to step in and monetarily support an entire second family.

Therefore, my Lolo’s quiet dream of becoming a physician was never actualized. And so became the impetus for his vocal expression of what he wanted me to actualize.

“You will become a brain surgeon,” was my Lolo’s oft-expressed mantra for me, beginning when I was nine. “You will become a brain surgeon.”

While some might take this mantra as pressure or hear the rhetorical nature of his statement as a demand, I heard it as a sentiment of what my Lolo believed I could be. What he believed I should be. What he knew I would be, because he believed in me.

And because he wanted me to rise above what he had hoped to, when he first journeyed to this country.

“You will be a brain surgeon.”

That sentiment was reinforced every time one of my Lolo’s brothers or sisters visited on their way to take a medical or nursing Board exam, or to begin a fellowship, or a new position at an esteemed medical institution. One after another sibling, who we would host by throwing a traditional Filipino celebration which always included whole roasted pig (with the men of the family “fighting” over who would get to eat the pig’s brain), and customary Filipino silk shirts worn by the men, including my Lolo, who would change out of his typical garden or flannel shirt, to applaud and toast yet another sibling who actualized their dream of becoming a medical provider.

Only years later, after my grandfather had passed and it was necessary to review his financial papers, did I learn the instrumental role that my Lolo had played in the actualization of his siblings’ educational dreams. Namely, that he had been sending money home to his family since the very first day he arrived in America. Money that was first used to help support his parents, and then money that was used to help support each and every one of his siblings’ college education.

“You will be a brain surgeon.”

My Lolo repeated this sentiment even when I told him of my dream to be a psychologist, and then again when I was formally accepted into college.

The last time I heard my beloved Papa repeat his favorite mantra, was when I came home for a visit during my first year of college. This time, proudly unfolding my first psychology paper, which had a 97% on the top page written in red.

“You will be a brain surgeon,” but this time his words were accompanied by a hearty laugh and a beautiful glint in his eyes which said, “I’m proud of you, granddaughter.”

That was the last time I saw my Lolo alive.

This past summer, as I married my second husband, a man so like my Lolo in his quiet introverted nature, keen intellect, and abundantly generous Spirit, my sister and I lit a candle for my Papa as the DJ played, “Planting Rice is Never Fun.”

Papa, thank you for all you’ve helped me to actualize. I promise to always remain a living manifestation of both of our dreams.

Dr. Julie T. Anné Zeig is a complex trauma and eating disorder specialist. She shared this candid historical blog as part of a book proposal in which “Write a personal description of what influenced you and your work” was requested. Dr. Julie is a culmination of many things that have influenced her and her work with passion, most importantly, she is a living manifestation of her Lolo’s dreams.

Follow Dr. Julie on instagram: @drjulietanne